Medieval ‘New England’: a forgotten Anglo-Saxon colony on the north-eastern Black Sea coast

Although the name ‘New England’ is now firmly associated with the east coast of America, this is not the first place to be called that. In the medieval period there was another Nova Anglia, ‘New England’, and it lay far to the east of England, rather than to the west, in the area of the Crimean peninsula.

The following post examines some of the evidence relating to this colony, which was established by Anglo-Saxon exiles after the Norman conquest of 1066 and seems to have survived at least as late as the thirteenth century.

| Despite the massive losses suffered at Senlac/Hastings, enough of the Anglo-Saxon nobility remained to put up serious resistance to Norman rule in several areas of England. It took several decades for it to become clear that William could not be thrown out, at which point the final wave of exiles left for the East |

The evidence for a significant English element in the Varangian Guard of the medieval Byzantine emperors has been discussed on a number of occasions. The Varangian Guard was the personal bodyguard of the Byzantine emperor from the time of Basil II (976–1025), founded to provide the emperor with a trustworthy force that was uninvolved in the internal politics of the Byzantine Empire and thus could be relied on in times of civil unrest. Whilst initially made up of Rus’ from Kiev, with Scandinavian warriors subsequently forming an important part of the guard through the eleventh century, from the late eleventh century onwards it had a significant English component too. Indeed, the ‘English Varangians’ appear to have continued to constitute a high proportion of the Varangian Guard right through the twelfth century and up until the siege of Constantinople in 1204, during the Fourth Crusade.(1) This is, in itself, of considerable interest, but even more intriguing is the question of why substantial numbers of English warriors entered the Varangian Guard in the later eleventh century, for the answer to this is thought to lie in a number of sources that indicate that there was, in fact, a sizeable emigration of Anglo-Saxons from England to Constantinople in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Key references to this post-1066 emigration from England to the Byzantine Empire include a brief account by Goscelin of Canterbury, written in the 1090s; another by the Anglo-Norman historian Ordericus Vitalis (b. 1075), written in the first half of the twelfth century; a more detailed narrative included in the Latin Chronicon universale anonymi Laudunensis, written by an English monk at Laon in the early thirteenth century; and a related, but probably not directly derivative, account in the Edwardsaga, or ‘Icelandic Saga of Edward the Confessor’ (Saga Játvarðar konungs hins helga), which is thought to have been composed in the fourteenth century but drew on an earlier text that may well have had its origins in the early twelfth century and be the source of the Chronicon Laudunensis too. Although a number of minor details—such as the name of the leader of the exiles and the exact route that they took to get to Constantinople—vary between the latter two accounts in particular, in general the available sources all paint a complementary and consistent picture.

According to these sources, what seems to have occurred is that, in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, a group of English lords who hated William the Conqueror’s rule but had lost all hope of overthrowing it decided to sell up their land and leave England forever. Led by an ‘earl of Gloucester’ named Sigurðr (Stanardus in the Chronicon Laudunensis), they set out with 350 ships—235 in the CL—for the Mediterranean via the Straits of Gibraltar. Once there, they voyaged around raiding and adventuring for a period, before learning that Constantinople was being besieged (either whilst they were in Sicily, according to the Edwardsaga, or in Sardinia, as the CL). Hearing this, they decided to set sail for Constantinople to assist the Byzantine emperor. When they reached there, they fought victoriously for the emperor and so earned his gratitude, with the result that they were offered a place of honour in his Varangian Guard.

This sequence of events appears to underlie all four of the sources mentioned above and is moreover supported by contemporary Byzantine sources too, as Jonathan Shepard has convincingly argued.(2) As to the date of this emigration of disgruntled Anglo-Saxon lords and their followers, Christine Fell makes a good case for it having taken place in the mid- to late 1070s, after the death of King Sweyn of Denmark in c. 1074 (who the English had hoped would come to their aid), with the Chronicon Laudunensis actually assigning a date of 1075 to the arrival of the English in Constantinople.

If so, then they arrived in the reign of Michael VII (1071–78) and the siege that they helped relieve was that of the Seljuk Turks, which occurred in his reign and would makes sense of the fact that the Edwardsagastates that Constantinople was being besieged by a ‘heathen folk’. The main objection to this is that both the Edwardsaga and the Chronicon Laudunensis both claim that the English arrived early in the reign of Alexius I Comnenus (1081–1118); however, as Fell points out, this does not fit with their description of the besieging of Constantinople by ‘heathen folk’ nor the Chronicon‘s stated date for their arrival. The simplest explanation is probably that the English emigrants arrived in the mid-1070s under Michael VII, relieving the siege by the Turks then, but their later extensive use by the more famous Alexius I Comnenus—as documented in Byzantine sources—led to the wrong name becoming attached to the reign in which they arrived.(3) With regard to their leader, the English form of the Edwardsaga‘s name Sigurðr was Siward/Sigeweard and is usually considered to be the original name attached to the tale, not least because the name Siward was borne by a number of high-status men in mid-eleventh-century England, unlike the Chronicon Laudunensis‘s Stanardus. Indeed, there were two English lords called Siward who are known to have joined Hereward the Wake’s rebellion in 1071, and it is by no means impossible that ‘Sigurðr, earl of Gloucester’ was one of these two, as a number of commentators have suggested, especially as one of them owned extensive lands in Gloucestershire.(4)

| A twelfth-century depiction of the Varangian Guard, from the Madrid Skylitzes (image: Wikimedia Commons). |

Thus far the story, as outlined above, is clearly intriguing, and moreover largely supported by all of the available sources, both northern and Byzantine. However, perhaps the most remarkable and interesting part of the tale is found only in the Chronicon Laudunensis and the Edwardsaga, both of which may derive from a lost early twelfth century account, according to Fell. The Edwardsaga states that whilst some of the exiled Anglo-Saxons accepted the offer of joining the Varangian Guard, some members of the group asked instead for a place to settle and rule themselves:

[I]t seemed to earl Sigurd and the other chiefs that it was too small a career to grow old there in that fashion, that they had not a realm to rule over; and they begged the king to give them some towns or cities which they might own and their heirs after them. But the king thought he could not strip other men of their estates. And when they came to talk of this, king Kirjalax [Alexius I Comnenus] tells them that he knew of a land lying north in the sea, which had lain of old under the emperor of Micklegarth [Constantinople], but in after days the heathen had won it and abode in it. And when the Englishmen heard that they took a title from king Kirjalax that that land should be their own and their heirs after them if they could get it won under them from the heathen men free from tax and toll. The king granted them this. After that the Englishmen fared away out of Micklegarth and north into the sea, but some chiefs stayed behind in Micklegarth, and went into service there.

Earl Sigurd and his men came to this land and had many battles there, and got the land won, but drove away all the folk that abode there before. After that they took that land into possession and gave it a name, and called it England [Nova Anglia, ‘New England’, in the Chronicon Laudunensis]. To the towns that were in the land and to those which they built they gave the names of the towns in England. They called them both London and York, and by the names of other great towns in England. They would not have St. Paul’s law, which passes current in Micklegarth, but sought bishops and other clergymen from Hungary. The land lies six days’ and nights’ sail across the sea in the east and north-east from Micklegarth; and there is the best of land there: and that folk has abode there ever since.(5)

Needless to say, the description of New England as lying ‘across the sea in the east and north-east from Micklegarth’ suggests that the lands that Alexius gave to the English exiles lay somewhere in the region of the Crimean peninsula. This is supported by the sailing time specified too, as the fourth-century AD ‘Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax’ estimates six days’ and nights’ sail as the length of the sea-journey from Constantinople to the western tip of the Crimean peninsula. Such agreement in these incidental details is, of course, interesting. So the question becomes, is there any other supporting evidence for the establishment of a ‘New England’ in the region of the Crimea by the Anglo-Saxon exiles who travelled to the Byzantine Empire in the late eleventh century?

Perhaps surprisingly, the answer to this question is a ‘yes’, as Jonathan Shepard has demonstrated in another important article.(6) First, there is evidence that the Byzantine Empire did indeed see a restoration of its authority in the Crimean peninsula and Sea of Azov area at the turn of the eleventh century, possibly after a brief period of Turkish influence there. Such certainly seems to be implied in the letters of Theophylact of Ohrid (d. c. 1107) to Gregory Taronites, and a contemporary eulogy of Manuel Straboromanus to Alexius I Comnenus alludes to his restoration of Byzantine influence in the north-east of the Black Sea by the Cimmerian Bosporus (the modern Kerch Strait on the east of the Crimean peninsula, leading to the Sea of Azov).(7)

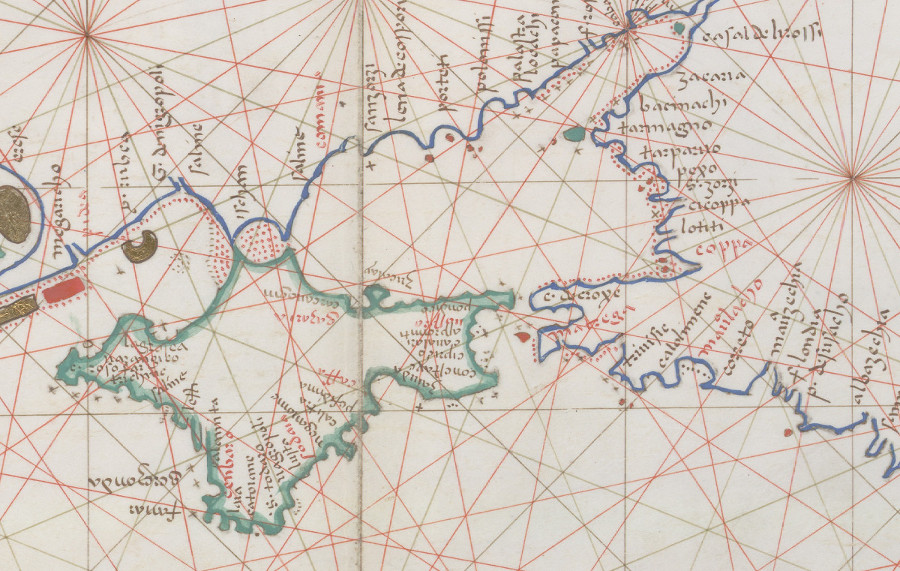

| Extract from an Italian portolan atlas of 1553, showing the Crimean peninsula, the Cimmerian Bosporus (Kerch Strait) leading to the Sea of Azov, and the north-east coast of the Black Sea; forms of the names Susaco, Londina and Vagropolis are included on this portolan (image: Wikimedia Commons). |

Second, there is actually place-name evidence from the Crimea and the north-eastern Black Sea coast that can be cited in support of the narrative offered in the Edwardsaga and Chronicon Laudunensis. This takes the form of five place-names that appear on fourteenth- to sixteenth-century portolans (coastal charts made by Italian, Catalan and Greek navigators) in the north and north-eastern portions of the Black Sea. Two of these names, Susaco and Londina, are of particular importance. Susaco—or Porto di Susacho—is found on the earliest charts, from the fourteenth century onwards, and is thought to involve the name ‘Saxons’, perhaps deriving from the Anglo-Saxon folk- and region-name ‘Sussex’ (the ‘South Saxons’).(8) Londina is found close to Susaco on the fuller, more detailed charts of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and has been plausibly viewed as being just what it looks like, a version of the English place-name ‘London’ (with this probably being applied originally to a city on the Black Sea coast and then transferred to an associated river—as sometimes occurs in with English place-names and river-names—hence the fact that the name Londina is frequently preceded by flume or flumen on the portolans). It need hardly be said that this evidence is of considerable interest in the present context, with these two names seeming to offer a significant degree of confirmation of both the Edwardsaga/Chronicon‘s general narrative of an Anglo-Saxon settlement of this area and the specific claim that:

To the towns that were in the land and to those which they built they gave the names of the towns in England. They called them both London and York, and by the names of other great towns in England.

As to the locations of both Susaco/Porto di Susacho and Londina, the portolans clearly map them on the north-east coast of the Black Sea, east of the Cimmerian Bosporus (Kerch Strait).(9) In contrast, two of the other three relevant place-names to be discussed here were located to the west of this strait, on the Crimean peninsula, and at least one other was located to the north on the Sea of Azov. All of these other names seem to ultimately have Varang- as their first element, taking the forms Varangolimen, Vagropoli, and Varangido agaria. The first of these, Varangolimen, contains the Greek word for a harbour and seems to indicate a port belonging to Varangians, and both it and the second, Vagropoli, are mapped on the Crimean peninsula itself, whilst Varangido agaria lay on the Sea of Azov, just to the south of the mouth of the Don river. Although all three of these Greek names refer only to Varangians and don’t replicate English place- or region-names, Shepard has argued persuasively that these three names are most plausibly linked to the ‘English Varangians’, rather than Scandinavian Varangians or Russians.(10) The implication of all this would thus seem to be that the Nova Anglia, ‘New England’, of the Edwardsaga/Chronicon Laudunensis did indeed exist and that it encompassed at least a number of cities stretching from the Crimean peninsula through to the southern shore of the Sea of Azov (described as ‘the Warang Sea’ in a Syrian map of c. 1150) and down the Black Sea coast east of the modern Kerch Strait.

| The Vulan River in Arkhipo-Osipovka, on the north-eastern Black Sea coast, which is sometimes suggested to be the location of the portolans’ Londina (image: Wikimedia Commons). |

Third and finally, there are independent historical references to a ‘land of the Saxi‘ (terram Saxorum) being in this part of the world in the thirteenth century, with the Saxi stated to be Christians and portrayed as dwelling in well-fortified cities. These references are found in the accounts of the Franciscan friars who were sent on a mission to the Mongols by Pope Innocent IV in 1246–7, and the consistent name of the Saxi in these accounts, the fact they are said to be Christians (rather than Muslims or pagans), and the implication that they lived in the area of the Crimea and/or around the Sea of Azov, combine to strongly suggest that the Saxi were, in fact, the Anglo-Saxons of ‘New England’, rather than any other people.

Needless to say, this is again important. Not only does the presence of the Christian Saxi in the area of the Crimean peninsula/Sea of Azov offer further support for the historicity of the Edwardsaga/Chronicon narrative, but it also suggests that the Anglo-Saxon exiles who reportedly founded ‘New England’ in c. 1100 continued to be identifiable as a separate people with their own ‘land’ as late as the mid-thirteenth century, which is interesting in itself. Indeed, they seem to have still been a military force to be reckoned with, to judge from the friars account of the Saxi‘s resistance to an attempted conquest of them by the Tartars:

When we were there we were told that the Tartars besieged a certain city of these Saxi and tried to subdue it. The inhabitants however made engines to match those of the Tartars, all of which they broke, and the Tartars were not able to get near the city to fight owing to these engines and missiles. At last they made an underground passage and bursting forth into the city they tried to set fire to it, while others fought, but the inhabitants posted a group to put out the fire, and the rest fought valiantly with those who had penetrated into the city and, killing many of them and wounding others, they forced them to retire to their own army. The Tartars, realising that they could do nothing against them and that many of their men were dying, withdrew from the city.(11)

Of course, such a survival of ‘New England’ into the thirteenth century is perhaps not entirely surprising if it did indeed exist, as ‘English Varangians’ were still identifiable as a distinct group at Constantinople into the thirteenth century. In fact, the continued existence of English settlements on the Black Sea coast might well help explain the continued presence of English Varangians at Constantinople, with this force perhaps being renewed in each generation from Nova Anglia. Indeed, the author of the Edwardsaga clearly thought that the descendants of the English exiles still lived there in the fourteenth century (‘that folk has abode there ever since’), and the mid-fourteenth-century De Officiis of Pseudo-Codinus related that the Varangians who existed then still constituted a separate people and that, at Christmas, they wished the emperor length of life ‘in their native tongue, that is, English’!(12)

In conclusion, the above points would seem to add some considerable weight to the case for the existence of a ‘New England’ on the northern and north-eastern coast of the Black Sea in the medieval period. Not only does it seem that the Byzantine Empire regained control of that portion of the Black Sea coast in this period, just as the Edwardsaga/Chronicon Laudunensis claim, but there also exists a quantity of medieval place-name evidence from this region that offers significant support for the establishment of English Varangian settlements there and a thirteenth-century account that appears to refer to the continued existence of a Christian people named the Saxi in this area, who occupied defended cities and were militarily sophisticated.

In such circumstances, the most credible solution is surely that the medieval tales of a Nova Anglia, ‘New England’, in the area of the Crimean peninsula and north-eastern Black Sea coast do indeed have a basis in reality. This territory would appear to have been established by the late eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon exiles who had left England after the Norman Conquest and joined the Byzantine emperor’s Varangian Guard, and their control of at least some land and cities here apparently persisted for several centuries, perhaps thus providing a regular supply of ‘English Varangians’ to the Byzantine Empire that helps to explain why the ‘native tongue’ of the Varangian Guard continued to be English as late as the mid-fourteenth century.

Notes

1. See, for example, C. Fell, ‘The Icelandic saga of Edward the Confessor: its version of the Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium’, Anglo-Saxon England, 3 (1974), 179–96; J. Shepard, ‘The English and Byzantium: a study of their role in the Byzantine army in the later eleventh century’, Traditio, 29 (1973), 53–92; and J. Godfrey, ‘The defeated Anglo-Saxons take service with the Byzantine Emperor’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 1 (1979), 63–74.

2. Shepard, ‘The English and Byzantium’, especially pp. 60–77; Fell, ‘The Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium’, 192–3.

3. Fell, ‘The Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium’, 193–4; Godfrey, ‘The defeated Anglo-Saxons take service with the Byzantine Emperor’, 69–70. Shepard, ‘The English and Byzantium’, 81–4, suggests an alternative scenario involving a feared, but never actually realised, siege of Constantinople by the Pechenegs, a Turkic people, in 1090–1. This has, however, failed to find much favour as a candidate for the siege that the English exiles relieved, not least because not only was it not an actual siege, but it also took place so long after the Norman conquest and the period of significant English resistance to the Normans (as Godfrey, for example, notes, pp. 69–70).

4. See further Fell, ‘The Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium’, 184–5, and especially p. 185, fn. 3, on the identification of Siward/Sigurðr and the potential solution to some of the issues with this.

5. G. W. Dasent (trans.), Icelandic Sagas: Vol. III. The Orkneyingers Saga (London, 1894), Appendix F, pp. 427–8. See Fell, ‘The Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium’, 189–90, for the relationship between the Edwardsaga and the Chronicon Laudunensis and the suggestion that both derive from a lost early twelfth-century source.

6. J. Shepard, ‘Another New England? — Anglo-Saxon settlement on the Black Sea’, Byzantine Studies, 1 (1978), 18–39. Much of what follows is based on this important but somewhat difficult to obtain article, which offers a convincing and in-depth analysis of the evidence for a medieval ‘New England’ in the region of the Crimean peninsula and the north-eastern Black Sea coast.

7. Shepard, ‘Another New England?, 21–6.

8. Shepard, ‘Another New England?’, 27–8; G. A. F. Rojas, “The English Exodus to Ionia”: the Identity of the Anglo-Saxon Varangians in the Service of Alexios Comnenos I(Marymount University MA Thesis, 2012), p. 50.

9. More exact locations are difficult: it has been suggested that the river that took on the name Londina was the modern Vulan and this is probably the most plausible solution, with Susaco then necessarily lying to the south-east of this on the basis of the portolan charts. On the other hand, one early nineteenth-century traveller seemed clear that, so far as he knew, the early eighteenth-century Turkish fortress of Sudschuk-ckala’h—Sujuk-Qale, built in 1722 and now the site of Novorossiysk, Russia’s main port on the Black Sea until 2014—was the modern descendant of the portolans’ Porto di Susacho. If so, then Londina can’t have been on the Vulan, as Sudschuk-ckala’h/Novorossiysk is located to the north-west of this river. See further Shepard, ‘Another New England?’, 27–8, and J. von Klaproth (trans. F. Shoberl), Travels in the Caucasus and Georgia, Performed in the Years 1806 and 1808, by Command of the Russian Government (London, 1814), pp. 264–5. Note, Susaco continued to be marked on maps of the region well into the eighteenth century; see, for example, Io Baptista Homann’s 1715–24 map Imperii Persici in Omnes Suas Provincias and Johann Gottlieb Facius’s 1769 map Carte exacte d’une Partie de l’Empire de Russie &c.

10. Shepard, ‘Another New England?’, 30–1.

11. C. Dawson (ed. and trans.), Mission to Asia: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New York, 1966), pp. 42 (quotation), 80. There is an extensive discussion of the various suggestions that have been made as to the identity of the Saxi in Shepard, ‘Another New England?’, 34–8, who demonstrates that none of the other candidates are really credible, given the name, faith, location and character of the Saxi in the friars’ accounts.

12. S. Blöndal & B. S. Benedikz, The Varangians of Byzantium (Cambridge, 1978), p. 180; Shepard, ‘Another New England?’.