Templar Book Week Kicks Off

Templar Book Week Kicks Off

Follow @KnightsTempOrgWith a stunning new book already at the printers, and another about to be typeset, the Knights Templars' venture into book publishing is proving a big success. The first two books in our Deus Vult series also continue to sell fast, and to get a great response from all who read them.

To celebrate this fact, we're making this week Templar Book Week. We'll be giving new readers of this site, and old supporters too, the chance to read sample passages or chapters from each book. Today we're starting with a chapter from our forthcoming book on Heroes of the English-Speaking World. This is a compilation of well-researched but concise essays on more than two dozen of the greatest heroes produced through a wide sweep of history by the nations of the British Isles, Ireland, the USA (including Jim Bowie, fighters of the War Between the States, Smedley Butler, Drew Dix and others), Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa.

Our Heroes book is a direct response to the bigots of the 'cancel culture' who are working overtime to demonise or kill the memory and glory of our nations' past - as part of their Long War to deny our children and grandchildren a future. It's thus not just a fine and entertaining piece of History, it's production and widespread distribution is also an act of resistance in a cultural war.

This book will be ready for sale this autumn, in plenty of time to buy it for Christmas. In the meantime, here's a sample chapter:

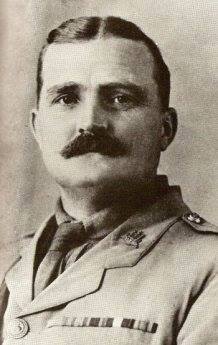

Jack Kelly

A surprising number of military heroes start out as unassuming men who quietly undertake to do their duty, then go on to do it in extraordinary ways. But some men are natural born fighters whose whole lives seem geared towards courting danger and performing feats of extraordinary valour almost as part of the job.

One such was John (Jack) Kelly. Later described as “Brave as a lion, stubborn as a mule and as quick tempered as his Irish forebears”, he was to achieve fame and a degree of notoriety for his mixture of heroic exploits and explosive temperament.

John Sherwood-Kelly was one of twin sons born on 13th January 1880 in Lady Frere, Cape Colony, South Africa. His father was of Irish stock and was a leading figure in the community. He had been the local mayor and a few years earlier had saved the lives of 25 people when the Italian ship, SS Nova Bella, ran into trouble at the St John’s river mouth.

Often called Jack by his family, the boy knew tragedy early in life. His mother – with whom he was very close - died when he was 12 and his twin brother was killed falling from a horse just a year later. His father subsequently married his governess, giving him three half-siblings.

Kelly was educated in boarding schools in South Africa. He was keener on sports such as horse riding and boxing, in which he excelled, than school work.

Jack was just sixteen when news arrived of a bloody rebellion in Matabeleland, where the British South Africa Company had established uneasy control and begun to encourage European settlement.

The BSAC Administrator General for Matabeleland, Leander Starr Jameson, had sent most of his troops and armaments in the ill-fated Jameson Raid against the Boer Republic in Transvaal. This had left the 4,000 settlers nearly defenceless. A rebel leader, M'limo, toured the native villages, preaching that the settlers were responsible for the drought, locust plagues and the cattle disease rinderpest ravaging the country.

M’limo promised that the bullets of the settlers would change to water and their cannon shells would become eggs. The warriors would slaughter the settlers in Bulawayo, then head out into the countryside and butcher all the others.

Many of the native police deserted and joined the rebels. The Matabele were armed with a variety of weapons, including rifles, assegais, knobkerries (heavy-headed fighting sticks) and battle-axes. As news of the rebellion spread, the Shona joined in the uprising.

Within a week, 141 settlers were slain in Matabeleland, another 103 killed in Mashonaland, and hundreds of homes, ranches and mines were burned. A particularly terrible case occurred at the Insiza River where Mrs. Fourie and her six small children were found mutilated beyond recognition on their farmstead. Two young women of the Ross family living nearby were similarly killed in their newly built home.

News of the atrocities outraged white South Africans and young Jack promptly enlisted in the British South Africa Police (BSAP), which was hastily expanded to march to the relief of the surviving settlers.

The settlers built a laager of sandbagged wagons in the centre of Bulawayo. Barbed wire entanglements were set up. Oil-soaked fagots were arranged in strategic locations in case of attack at night. Explosives from mining supplies were hidden in buildings outside the defence perimeter, to be detonated if the enemy occupied them.

The younger boys were set to work collecting glass bottles, breaking them into shards spread in front the front of the wagons to hinder any charge by the barefoot Africans. The men had few weapons except for their hunting rifles, although there were a few artillery pieces and a small assortment of machine guns.

Rather than wait passively, the settlers mounted patrols, called the Bulawayo Field Force. These rode out to rescue surviving settlers in the countryside. The renowned big game hunter Frederick Selous raised a mounted troop of forty men to scout southward into the Matobo Hills. Maurice Gifford, along with 40 men, rode east along the Iniza River. Parties of settlers were escorted to Bulawayo. It was dangerous work; within the first week, 20 men of the Bulawayo Field Force were killed and 50 were wounded.

Wary of the settlers’ machine guns, 10,000 Matabele warriors laid siege to the settlement, where nearly 1,000 women and children were crowded in increasingly desperate conditions.

A southern relief force, which included Jack Kelly, was nearly ambushed, but the trap was spotted by Selous and the attackers were driven back.

With the siege broken, 50,000 Matabele retreated into their stronghold of the Matobo Hills. The fierce fighting was ended when two British officers crept into the middle of the Matabele army and assassinated M’limo.

Cecil Rhodes now set out on his one-man mission to persuade the Matabele to lay down their arms and bring the rebellion to a close. The Bulawayo Field Force was disbanded on 4th July 1896 and the South African volunteers headed home.

Kelly joined the Cape Mounted Police. Then, at the outbreak of the Boer War in 1899, he enlisted in the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers. The Boers laid siege to the town of Mafeking, where a small force of British soldiers commanded by Colonel Robert Baden-Powell held out for 217 days until relieved by a force led by Colonel Plumer’s Column, in which 20-year-old Kelly served as a Trooper.

In January 1901 John was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Imperial Light Horse and later joined Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts as a Lieutenant. The recklessly brave young horseman saw action in Rhodesia, the Orange Free State and Transvaal. He was twice mentioned in despatches by the time the outnumbered Boers sued for peace in May 1902.

In 1904 Kelly was reduced to a Trooper again – probably as a result of his notorious quick temper and tendency to question authority - and returned to South Africa, where he worked as a trade with his father’s store.

Jack quickly found it crushingly boring and joined a force largely consisting of his former Boer opponents, who had volunteered to fight for the British Empire in Somaliland.

The Muslim Somalis had risen in revolt under Mohammed Abdulle Hassan, the so-called "Mad Mullah". The Somaliland Burgher Contingent was the first South African volunteer unit to fight on foreign soil. Although mainly Boers, it included English-speaking South Africans as well as men from England, Rhodesia, America, Ireland, Scotland, Canada and Australia. All of the 100-strong Corps brought their own horses.

Jack and his fellow adventurers endured many hardships during the campaign: they had to march through dense bush, in extreme heat, with meagre rations and very little water. The Somaliland Burgher Contingent was involved in skirmishes with the Dervishes who, although outgunned, were ferociously brave opponents.

Kelly was promoted to the rank of Sergeant before the conflict ended the following year and he returned to South Africa.

In 1906 he took part in the suppression of the Bambatha Rebellion. The Natal Zulus had been angered by the imposition of a poll tax designed to force subsistence farmers to go to work on white-owned farms.

Chief Bambatha became the focus of the unrest, gathered together a small force of supporters and began launching a series of guerrilla attacks.

Jack Kelly was with the force that took on the rebels. The Zulus lost between three and four thousand dead, against a mere 36 government troops. The rebellion crushed, Jack found work recruiting labour for the mines in the Transkei.

In 1912 the Irish Home Rule crisis exploded and the call went out for “all unionists” to return to Ireland. Despite their Irish family origins and staunchly pro-Empire views, Jack and his younger half-brother Edward travelled to Ireland and they joined the Ulster Volunteer Force, which was being organised in order to fight both the Irish nationalists and the British Army for the right of Ulster to remain British.

With war clouds gathering over Europe, the Irish crisis faded and Jack moved to England. He met a young beauty named Nellie Crawford and found work as a housemaster at Langley School in Norfolk. He joined the recently formed Territorial Force and was a towering inspiration for the boys of its Officer Cadet Corps.

At the outbreak of war, Jack joined the 2nd Battalion King Edward’s Horse as a Private, but with his extensive military experience and imposing figure he was quickly promoted to 2nd Lieutenant.

Kelly was transferred to The Kings Own Scottish Borderers, whose Regimental Diary recorded his arrival in July 1915: “Today a new major joined us, a Herculean giant of South African origin with a quite remarkable disregard for danger.”

The Borderers were shipped to Gallipoli, where Kelly’s lungs were badly burned in a Turkish gas attack. He spent a week in hospital before returning to the front line. There he led his men in a frontal attack on a Turkish trench. Only six men returned and Kelly was wounded three times. He won the Distinguish Service Order –the first awarded to a South African during World War One.

During his leave to recover from his wounds, Jack married Nellie.

Early May 1916 saw Kelly given command of the 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers as part of the 29th Division preparing for the Battle of the Somme.

Leading his Battalion from the front during fighting at Beaumont Hamel, Kelly was shot through the lung. A stretcher-bearer named Jack Johnson rescued the badly wounded officer under heavy fire. The ‘Blighty’ wound saw him evacuated back to London.

Once he had recovered, Kelly spent the summer on a recruiting tour in South Africa, where he got a hero’s welcome. On his return, Jack was presented with his Distinguish Service Order by King George V in November 1916.

He was then posted to the 3rd Battalion Kings Own Scottish Borderers as a Major, but very soon after arriving back in France he requested a transfer to the 10th Norfolk Reserve Battalion.

On 1st January 1917, Kelly’s recruiting efforts were recognised with the award of the Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George, Third Class or Companion, abbreviated to CMG. In February 1917 he was again posted to the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers as Officer Commanding.

1917 saw Kelly and his men take part in offensives on various sectors of the Western Front, including Vimy, Arras, Ypres and Passchendaele. November saw a fresh push planned at Cambrai, using the new weapon “the Mark 1 Tank”. The Inniskillings were in the thick of the fray and Jack’s actions on the opening day of the battle earned him the Victoria Cross. The citation reads as follows:

“For most conspicuous bravery and fearless leading when a party of men of another unit detailed to cover the passage of the canal by his battalion were held up on the near side of the canal by heavy rifle fire directed on the bridge. Lieutenant Colonel Sherwood-Kelly at once ordered covering fire, personally led the leading company of his battalion across the canal and, after crossing, reconnoitred under heavy rifle fire and machine gun fire the high ground held by the enemy.

“The left flank of his battalion advancing to the assault of this objective was held up by a thick belt of wire, where upon he crossed to that flank, and with a Lewis gun team, forced his way under heavy fire through obstacles, got the gun into position on the far side, and covered the advance of his battalion through the wire, thereby enabling them to capture the position.

“Later, he personally led a charge against some pits from which a heavy fire was being directed on his men, captured the pits, together with five machine guns and forty six prisoners, and killed a large number of the enemy.

“The great gallantry displayed by this officer throughout the day inspired the greatest confidence in his men, and it was mainly due to his example and devotion to duty that his battalion was enabled to capture and hold their objective”.

Kelly was again injured in a gas attack and sent to recuperate in London. There he was presented with his VC by King George at Buckingham Palace on 23rd January 1918.

He was sent on a second South African recruiting tour. Following a speech in East London in the Eastern Cape, Kelly was reported and recalled back to England. In August 1918, Jack was put in charge of the troop ship HMS City of Karachi carrying new recruits to France. During the voyage, however, the officers revolted against what they described as Kelly’s bullying manner and derogatory statements about the troops.

Kelly apologised and narrowly escaped a court martial, serving the rest of the war as Officer Commanding the Norfolk Yeomanry.

While the majority of the British Army was rapidly demobilised after the Armistice, Kelly was among those sent to fight against the Bolsheviks who had seized control in Russia. In June 1919 he was in command of the second battalion of the Hampshire Regiment when he halted an attack on the Red forces at the village of Troitsa.

According to Kelly's account given shortly after to his brigadier, a series of factors accounted for his withdrawal: slow and difficult approach through marshy woods, lack of information about the progress of other columns, stiff resistance by the enemy, the danger of encirclement and lack of ammunition.

His furious commander, Field Marshal Lord Ironside, initially directed that Kelly be sent home for demobilisation. But the Brigade Operation Report concluded that Kelly's column at was successful at first but then withdrew as he considered the position insecure and was having difficulty obtaining ammunition supplies.

Ironside changed his mind, but a second clash with authority was shortly to end Kelly’s military career.

Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for War, decided to employ new variants of gas against the Bolsheviks in the North Russian theatre. As a trial of the new weapon Kelly was ordered to carry out a raid on the Bolsheviks under cover of a large discharge of gas. Kelly objected, partly against the use of gas, but primarily to the raid itself, which he regarded as pointless.

The gas raid never took place and Kelly was replaced as commanding officer of his unit and sent back to Britain for having "remarked adversely on matters of military import", criticised his superiors and divulged military secrets in a letter to a friend in England.

On his arrival back in Britain, Kelly wrote letters to the Daily Express and Sunday Express, which opposed the North Russia Campaign. The government urgently considered a court martial for Kelly over the letters but there were concerns that this “would be an unusual disciplinary procedure for an officer, rare for one of Kelly's rank, unprecedented for one so well decorated, four times wounded (twice gassed) and nine times mentioned in despatches."

But after the publication of another Kelly letter, a furious Churchill demanded the whistle-blower’s swift court martial. Kelly was arrested and tried in Westminster Guildhall on the charge of having written three letters to the press.

Kelly pleaded guilty to contravention of the King's Regulations which provided that an officer was "forbidden to publish in any form whatsoever or communicate, either directly or indirectly, to the Press any military information or his views on any military subject without special authority."

Kelly’s plea in mitigation concluded, “I plead with you to believe that the action I took was to protect my men's lives against needless sacrifice and to save the country from squandering wealth it could ill afford."

He was severely reprimanded. Two weeks later he relinquished his commission, although he retained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Pursued by a neglected wife and various creditors, he was unsuccessful in his many attempts to re-enter the army and was rejected by the French Foreign Legion.

As a noted war hero, however, Kelly remained popular with the public. He was selected to stand for the Conservative Party at two general elections for the mining constituency of Clay Cross in Derbyshire. His controversial and outspoken style struck a chord even among hardened socialists.

During one of the rallies, a woman came up to Nellie and introduced herself as the mother of Stretcher Bearer Jack Johnson. A meeting was arranged between the two men. In an interview with the Derbyshire Times, Kelly said it involved a “good deal of handshakes and some tears”.

He was defeated in the December 1923 election by 6,000 votes but reduced this by half in the election of October 1924. During the contest Kelly again hit the national headlines, having soundly thrashed some Communist hecklers.

In later years, Kelly worked for Bolivia Concessions Limited building roads and railways across Bolivia and went big game hunting in Africa. There he contracted malaria, from which he died in 1931. He was granted a full military funeral and buried at Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, England.

|

|